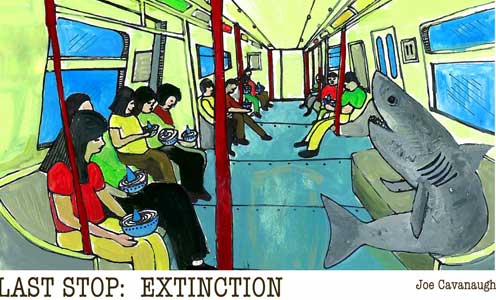

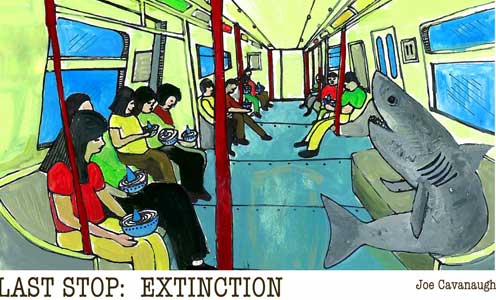

The following is a guest blog post by SCB member Joseph Cavanaugh, a natural resources specialist and marine scientist. Guest blog posts present interesting opinions and science-based perspectives that Society members might find thought-provoking. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of SCB.

|

In early 2013, my passion for sharks sunk into the quagmire of the worldwide shark finning crisis. I realized for the first time that in the abrupt future our oceans could be absent sharks. As a marine scientist, I understood the dire consequences of losing the oceans’ sharks. As an avid diver I was always struck by the glaring contrast between the invincible profile sharks presented and their true fragility. I needed to act, so I launched a crowd-funding (Kickstarter) campaign to raise funds to go to Hong Kong to investigate the status of the shark fin trade where more than 50% of the world’s fins transit through on their way to China’s mainland. I exhausted my vacation time in one fell swoop meeting with scientists and NGO leaders to better comprehend this seemingly intractable problem and determine whether conservation efforts in Hong Kong could muster hope of winning this battle to end shark finning. Hope, I found, comes in surprising packages.

Shark Finning

Sharks have graced the world’s oceans for some 450 million years, a span measured in geological time but difficult to grasp in terms of a fleeting human lifespan by comparison. How then have we forced this juggernaut of extinction on sharks, a family that predates bony fishes and whales, has survived several prior mass extinctions including that of the dinosaurs, and roamed the oceans before the separation of the continents from a single land mass called Pangaea? The short answer is that overfishing of shark species to supply an insatiable demand for shark fin soup in China has decimated shark populations worldwide in recent years. This demand for shark fin soup in China, her satellites and other Chinese communities has facilitated a particularly destructive and wasteful fishing method, shark finning, the act of fishing sharks primarily for their fins alone. After capture, the fins are sliced off and the sharks' thrashing bodies are discarded into the water where they sink and slowly bleed to death. The best estimates today are that upwards of 100 million sharks are killed each year worldwide primarily supplying shark fins for soup but also for traditional Chinese medicines, shark liver oil, shark cartilage, and aphrodisiacs.

|

|

Dried shark fins in the background in a market in Hong Kong |

Once the province of Chinese nobility, shark fin soup became widely available to an emergent middle class over the last fifteen years. Serving shark fin soup at a wedding banquet, for instance, shows off a father’s prosperity and generosity to his guests and celebrates his good fortune after a lifetime of hard work. The de rigueur fin itself confers no taste to the clear soup but prominently displayed atop the bowl is a symbol of conspicuous consumption, an auspicious display of the host’s social status. The soup, typically a broth thickened with chicken, ham and MSG, has the shark fin either shredded like vermicelli or merely served whole atop the bowl. The cost ranges from $25 to over $2,000 per bowl depending on the event, location, and species of shark served. Contrary to the folklore of traditional Chinese medicine, associating shark fin with a salubrious diet, shark fins have high concentrations of methyl mercury and are anything but healthy to eat.

Prior to Chinese trade opening with the west in the 1970’s and with the Nixon Administration in the U.S., China’s shark finning was restricted to her sovereign waters. Few Chinese could afford shark fin soup served at special celebratory banquets dating back to the Sung Dynasty (AD 978). Move forward a thousand years. China’s burgeoning trade with Europe and the U.S. in the 1970’s and 1980’s and a growing middle class with a significant boost in spending power in the 1990’s and 2000’s, caused demand for shark fin soup to surge, opening the floodgates for shark finning worldwide. The movie, Jaws, released in 1975 and coinciding with China's trade expansion, provided an unwitting catalyst in the race toward sharks demise by instilling in the mind of the public an image of the shark as a nearly invincible, mindless, man-eating machine—a creature we would be safer without. These attitudes helped shape fishing policies by allowing countries to sell sharks to Asian and European fishing fleets with little public backlash, also creating the misconception that shark species could withstand worldwide fishing pressure without consequence.

Traditionally, sharks were a nuisance bycatch until the shark finning industry emerged en force commanding high market value for fins easily stowed aboard ship. The fact that sharks were not readily identifiable as intelligent with elaborate songs like the humpback whale or the endearing permanent smile of bottlenose dolphins forestalled any serious conservation movement for sharks. In part as a response to Jaws, hundreds of annual shark fishing tournaments erupted in the U.S. in the 70’s and 80’s with many offering prizes for the largest and most sharks killed. Great numbers of sharks were also tolerated as incidental catch in numerous fisheries during the decades following Jaws and shark populations quickly plummeted. The general public had no idea outside of perhaps a select Cousteau audience, of the vital role sharks played in the ocean ecosystem.

Currently about 125 nations in the world supply China with shark fins in a labyrinth of legal, illegal, unregulated, and unreported supply chains. The shark fin industry accounts for approximately $360 billion dollars in annual trade revenue. Until very recently, directed shark fishing or indirect fishing as incidental catch from other fisheries was almost completely unregulated. The largest suppliers in the shark fin chain that predominantly runs through Hong Kong are Spain, Singapore, Taiwan, Indonesia, United Arab Emirates, Costa Rica and in the last few years increasingly, India. Surprisingly, the U.S. was the seventh largest exporter of shark fins to Hong Kong in 2008 according to a 2010 Oceana report. More than 50% of the annual trade in shark fins worldwide moves through Hong Kong as the epicenter en route to China’s mainland. The predominant species used in shark fin soup are blue, shortfin mako, silky, dusky, sandbar, tiger, smooth and scalloped hammerhead, great hammerhead, thresher, bull, and oceanic whitetip sharks. Dozens of other species are exploited including great whites, whale sharks and basking sharks, all protected species under the IUCN. Oceanic whitetips are likely 99% depleted and functionally extinct.

Fishers now ply every ocean and the most remote locations including seamounts and even marine protected areas to supply shark fins to China. With almost no markets for unsavory shark meat that is high in uric acid, the incentive for fishers is to remove the high value shark fins from any shark caught, live or dead, whether purposefully captured or caught incidentally, and save space in limited vessel storage by discarding the rest of the shark. Shark fins make up only about 5% of a shark’s body weight but high market demand places the incentive on shark fins thereby decimating shark populations in a ghastly and wasteful practice.

The U.S. and Canada have also been complicit in this trade but recent state- and province-wide bans in shark fin soup and legislature to end finning in Canadian and U.S. territorial waters is reversing the tide on this ghoulish trade. Shark Savers, WildAid, WWF, Oceana, Humane Society, and other groups’ steadfast efforts in the U.S. have led to state shark conservation laws in support of the federally mandated Shark Conservation Act passed in 2010 by Congress. The U.S. has banned shark finning in in U.S. waters since 2000. Currently, California, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, New York, Oregon and Washington have shark finning bans in state waters and do not allow trade in or consumption of shark fins. In 2009, Claudia Li started a Canadian based NGO, Shark Truth, that jumped out ahead of the curve in targeting the Chinese cultural acceptance of serving or consuming shark fin soup in Chinese communities across Canada. This laid the foundation for change in cultural acceptance of shark fin soup and led to province-wide bans in shark fin soup and products.

|

|

Shark fins conspicuously advertised in Hong Kong |

A Critical Point in Time

As recently as 15 years ago our estimates on the annual number of sharks killed were nascent. The first clear picture of how many sharks are killed annually came from then Ph.D. student Shelley Clarke. Dr. Clark’s dissertation began in 2000 when she attempted to answer this question. She spent a couple of years collecting data from Hong Kong seafood auction houses and fishing ports in Taiwan along with conducting some statistical analysis to fill in the gaps before delivering the first credible worldwide estimate that approximately 38-73 million sharks are killed each year, primarily for their fins. Clarke’s published research in 2004 sounded the alarm for governments and non-government organizations to recognize the gravity of the shark slaughter. Soon afterward, research estimated upward of 90% of large predatory fish species such as billfish, tuna, and sharks had been eradicated since the 1950’s. And the latest estimate on the annual number of sharks killed each year tops over 100 million from about 1.4 million tons annually harvested. Most of these sharks are finned. Historically, only small local markets existed for shark meat and typically the meat is worthless for resale so only the fins are kept and these are inconspicuously small for storage by comparison to the whole shark. World fishery statistics on shark landing remain elusive, in part because the Chinese government is a recidivist offender in fabricating their fishery landing data including sharks in an effort to lowball their GDP derived from fisheries. Smoke and mirrors reporting of fishery landing data and shark landing data in particular has skewed world fishery data since China now consumes more than 50% of the annual world fisheries catch and greater than 90 percent of sharks fished supply China.

Ecological Heavyweights

It may not be intuitively obvious why sharks are intrinsically vulnerable to exploitation from overfishing. As any top predator in the ocean or on land, there needs to be more prey than predators to keep a healthy ecosystem balance. Over 450 shark species in the world fill various trophic niches mostly as top predators. Although there are some natural predators to sharks, particularly when sharks are most susceptible to predation as juveniles, once mature, sharks have few natural predators. Sharks generally take many years to reach sexual maturity, reproduce infrequently, have long gestation periods, and produce relatively few young over their reproductive lifespans. As such, most shark species make a significant energy investment in reproducing a small number of large, viable young, selecting traits that confer quality over quantity, traits that identify most species of sharks by what ecologists term k-selected species. K-selected species like sharks are particularly vulnerable to commercial exploitation since they are unable to quickly replenish their populations during and after commercial harvesting.

Currently, we are fishing sharks that are top predators as if they were much further down the food chain like herring with magnitudes of order greater population numbers. Equally troubling is that more sharks are killed incidentally in long line fishing than are killed in all other targeted fisheries combined. Long lining is the practice of setting out miles of lines beneath the surface with thousands of baited hooks that indiscriminately target hundreds of species (e.g., sharks, sea turtles, marine mammals, etc.) in addition to what fishers are targeting, swordfish or tuna, for instance.

Approximately 5 million hooks are strewn out over 100,000 miles everyday in the world’s oceans. Not only are reproductively mature adults of non-target species killed in long line fisheries but millions of immature individuals of all species are killed as well. For sharks this is particularly worrisome because many species such as great whites, tiger, and reef sharks take decades to reach reproductive maturity. Aside from a slow reproductive capacity to meet rapacious fishing demand, most sharks are particularly vulnerable to coastal fishing because of their near shore life histories. Most shark species reproduce in shallow coastal waters where they are susceptible to overfishing and habitat destruction of their nursery areas in addition to coastal pollution and other threats. Climate change is accelerating marine habitat shifts that further challenge sharks’ foraging and reproductive success, leaving very little time for them to successfully adapt to a rapidly changing seascape.

Overfishing has likely already compromised the ability of dozens of shark species to replenish and even for those species with enough individuals left to restock their populations, this will take hundreds of years because of their long generational succession times. For many species, we are gazing upon living fossils, just as we might look to the night sky and see the light of a star that long-since went super nova. We may see remnants of many shark species for some short time into the future but without any appreciable populations to rebuild, these species are already on an irreversible path toward extinction. Fishery data where available show shark landings plummeting worldwide and an alarming increase in the percentage of immature sharks of all shark species rounding up the annual world catch.

Sharks are critically important to maintaining healthy ocean equilibrium. Without sharks, the inherent balance established over evolutionary time between predators and prey will be lost forever. For every food web connection marine scientists identify, probably hundreds more elude us. We know that trophic cascades occur when top predators like sharks are removed from an ecosystem. A trophic cascade is a phenomenon whereby a series of dramatic changes occur to relative predator and prey densities triggered by the addition (e.g., invasive species like the red lionfish in the Caribbean Sea) or removal of a predator species. The resulting changes to the remaining predator and prey interactions often cascade out of balance. Cynically, one might argue that other fish-eating species should fill in the niches vacated by sharks. But it’s not that simple, these trophic niches established themselves over millions of years. And the concomitant exploitation by humans of enormous numbers of species at all trophic levels is currently occurring worldwide in the oceans. Overfishing and destructive fishing at all trophic levels, pollution, habitat destruction, and the intractable problems climate change creates, are together reaping havoc on ocean ecosystems. Although ending the senseless slaughter of sharks primarily to satisfy one conspicuous consumption market is one problem we can solve with enough political willpower.

Tipping the Scales Back in Favor of Sharks

Today there is some room for cautious optimism that many shark species might be saved from extinction. The recent efforts over the last five years of several non-government organizations in Hong Kong in particular have begun changing cultural perceptions of sharks in Hong Kong and China’s mainland. As a result, demand for shark fins declined throughout Hong Kong and China by 50-70% in 2013. Although some portion of this decline may be due to a precipitous drop in shark landings worldwide and the increased fishing efforts necessary to find sharks to fin. Shark Savers, Hong Kong Shark Foundation (HKSK), WWF, WildAid, AquaMeridian and many other non-government organizations are working tirelessly to change the cultural acceptance of shark fin soup, making it increasing unfashionable to serve the dish at weddings and banquets. These groups’ efforts have led to announcements by both Hong Kong and Beijing governments in 2013 to ban shark fin soup at official functions. In addition, the work of HKSK and Shark Savers has similarly made it passé to serve shark fin soup at commercial bank and business functions. Shark Savers Hong Kong merged with WildAid (February 2014) to combine attributes that should bolster their effectiveness.

The most recent ad campaign by Shark Savers Hong Kong before the merge called, “I’m Finished with Fins”, has had incredible success in Hong Kong, Singapore, Taipei, and Beijing in making shark fin soup unsavory. The ads feature prominent Asian celebrities posing for portraits with fingers or hands crossed in front of their mouths symbolizing their pledge not to eat shark fin soup. Commercial airlines are increasingly banning shark fins as cargo and major hotel chains are banning the soup from the tens of thousands of banquets they host. An increasing number of countries are banning shark finning in their exclusive economic zones (200 mile sovereign waters) and more still are legislating that fishing vessels must land whole sharks in port, not just the fins, a measure that not only reduces take of sharks but also facilitates more accurate reporting, a task made very difficult with only fins landed. Across the board genetic testing on fins to identify shark species is on the horizon and will aid law enforcement immensely.

A most unlikely alley, the Communist party in Beijing may have the trump card in reversing the shark fin soup trend through their recent (2013) announcement to ban shark fin soup at official government functions. Capable of strict law enforcement and very little culpability to justify their actions, the centralized Communist party has great power to act. Interestingly, the current attitude in Beijing on banning shark fin soup has less to do with conserving sharks than ostensibly combatting an increasing trend toward ostentatious government spending. Beijing would also like its emerging middle class to spend less on costly foods and liquors and other luxury items and instead save more from their hard earned salaries. Whatever Beijing’s true motivation, sharks will benefit from a top down government ban on shark fin soup that may yet crossover to the vast middle class.

In 2013 there was upwards of a 70 percent decline in shark fin imports in Hong Kong according to the Hong Kong Census and Statistics Department. However, total worldwide landings are falling rapidly, making it increasingly difficult to meet demand. A couple of recently published papers on shark populations forecast dire declines for sharks worldwide and remember even mildly depleted stocks will take decades to replenish. One example of this comes from U.S. exploitation of sharks. For several decades, the Ocean Leather Company started in 1917 in Newark, New Jersey, enjoyed a monopoly on harvesting sharks along the eastern seaboard for leather and shark liver oil as a source of vitamin A and D and as manufacturing machine lubricant. Tens of thousands of sharks were harvested each year over their long history before closing operations in 1964. Fifty years later, a few species are just now showing signs of very modest population increases after so many years of over-harvesting, proof of their slow reproductive capacity mentioned earlier.

Apparently many people in China until very recent advertising campaigns by WildAid and Shark Savers were unaware that harvesting shark fins harms sharks or even that shark fin soup has shark fin in it. How is that possible? One reason is that the character for shark is not in the Chinese name, Yu Chi, which literally translates into fish wing in English. In 2010, the Bloom Association commissioned the University of Hong Kong Social Sciences Research Center to carry out a survey on consumption habits of shark fins and shark-related products in Hong Kong. This was the most comprehensive assessment of its kind with over 1,000 interviews conducted. Almost 39% of respondents were unaware that shark fins are sometimes obtained by cutting fins off live sharks and the de-finned sharks are thrown back into the sea. About 17% of respondents believed that sharks could survive after being finned and 9% believed shark fins grow back post-finning. However, restaurants and markets such as Sheung Wan in Hong Kong prominently display shark fins in their storefront windows so the disconnect between the fins and source is evident. Also, attitudes on China’s mainland regarding sharks are most certainly more naïve and ignorant to their plight because of restricted access to information and limited shark conservation campaigns until recently. A similar disconnect may exist if Westerners were polled about the origins of veal.

I’m FINished with Fins

We need a neoteric outlook on not just shark finning but on commercial fishing practices worldwide. The immediacy of a fresh approach cannot be overstated. With fish stocks plummeting worldwide, habitat destruction, pollution from plastics, fertilizers, pharmaceuticals, oil and natural gas extraction, we are straining the resiliency of the oceans to repair themselves for future generations. Sustainable fishing is a misnomer when it comes to sharks because their life-history strategies do not support targeted extraction, especially given that more sharks are landed indirectly as bycatch than in directed shark fisheries. The incidental capture of sharks maintains opportunistic revenue for fishers as long as a market exists for fins. Almost all fished species of sharks are highly migratory species. They cross international waters where few regulatory laws exist in a confounding mishmash of regulatory agencies governing state, national, and international jurisdictions where large regulatory loopholes exist making compliance and enforcement nearly impossible. Shark finning exemplifies the tragedy of the commons where short-term gain from plundering a resource without any accountability to the future is the rule.

The discovery in January 2014 of a prolific shark finning warehouse in Zhejiang Province in southern China tells us we have a long way to go. This factory processed more than 600 whale sharks in 2013 for fins as well as shark liver oil. Other species are also processed there such as great whites and basking sharks, species that are protected under CITES. As shark species and other high value fish such as Bluefin tuna become increasingly hard to find, their value climbs to extortionate levels that promote even greater exploitation. In the case of Bluefin tuna, subsidiary companies of Mitsubishi are deep freezing Bluefin for extinction where these companies will command the market price they want. As WildAid spokesman and former NBA basketball star states in a recent PSA, “when the buying stops, the killing can too.” All consumers are now complicit in world fishery demise but China more so than any other now by the shear magnitude of their fish consumption.

|

|

Shark Savers "I'm Finished with Fins" outreach walk in Hong Kong, July 2013 |

Recently, Palauan President Tommy Remengesau Jr., made an important announcement. A former fisherman himself, Remengesau saw precipitous declines in the number and sizes of sharks and groupers on the Palauan reefs. These declines are directly related to shark fishing licenses granted to foreign fleets that have decimated sharks and other marine species in Palau. Palau’s President took the most forward-thinking step he could and in January 2014 banned all shark fishing of foreign fleets from Palauan territorial waters. Once fishing rights expire later this year with Japan, Taiwan, and some private companies, fishing will only be allowed by Palauans and tourists and then only hook and line fishing. President Remengesau realizes that tourism revenue gained from healthy shark populations far surpasses revenue from fishing agreements. The only viable long-term option for healthy reefs surrounding the 370 square km protected area must protect shark and fish populations that in turn will further boost tourist revenue and maintain healthy coral reefs.

The government of the Bahamas similarly restricts all shark fishing in their waters and follows a recent FAO economic calculator that a live shark is worth over a million dollars to tourism and a dead shark yields only $150. Shark lovers from around the globe head to the Bahamas for incredible shark diving experiences and the Bahamian government purports enormous returns on investment in shark and marine sanctuary protection. And in February 2014, the Indonesian Government announced more good news in the creation of the largest sanctuary in the world for manta rays excluding all manta ray fishing within the country’s EEZ. Manta rays are another highly exploited species primarily for their gill rakers.

The immensity of consumer demand for natural resources China now exerts whether for shark fins, tiger parts, elephant tusks, rhino horns, sea cucumbers, raw building materials, minerals, is staggering and on an unprecedented scale. There is an urgency to ending traditions such as shark fin soup quickly to ensure the next generations do not opt for conspicuous consumption items like shark fin because these generations have magnitudes of order greater spending power than the generation born of the Cultural Revolution in 1966. Hong Kong itself has an alarmingly high seafood footprint consuming approximately 62kg of seafood per person annually, almost four times the world average. Ninety percent of the seafood consumed in Hong Kong is imported and the abundance of seafood in the markets and restaurants gives residents a false sense of seafood abundance. Recently, NGOs such as HK Shark Savers and HKSF began successfully rallying local Hong Kong chefs and some celebrity chefs like Gordon Ramsey to promote sustainable seafood dishes in lieu of shark fin soup. Remember that sustainable consumption for the world now hinges itself on the magnitude of consumption China exerts on world fisheries.

Continued and increased efforts are necessary by Asian NGOs that educate consumers about the misconceptions of traditional foods and remedies that use threatened and endangered species triggering enormous ecological costs. Renewed efforts are also needed with trade agreements to bolster existing regulations over shark fins and other shark products. The U.S. government is currently negotiating with Pacific Rim nations to develop the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade pact. Signatory nations must convince, coerce, cajole, and do whatever it takes to let all participating countries know that it is in theirs and all of our long-term interests not to allow shark finning or shark fin trade of any kind. The shark fin market will become one of black market trade as legitimate demand wanes in China. Accurate trade reporting by China would go a long way in developing trade restrictions and identifying supply routes and regulatory and enforcement gaps in trafficking shark fins worldwide. Over $3 trillion dollars in goods and services are annually derived from our oceans and shark products make up possibly a sixth of that trade. The oceans are critically important in regulating our climate, providing us with oxygen, and will offer us a veritable pharmaceutical bonanza in the near future. Sharks play an incalculably large role in regulating ocean health. Tipping the scale back in time to save sharks is the only way forward in a world increasingly more reliant on ocean resources with 3 billion people consuming seafood worldwide. China will be a major beneficiary of shark conservation if she can stifle the shark fin market and quickly reverse the unsustainable exploitation of sharks worldwide.

President Xi Jinping took the surprising first step in banning shark fin soup from government functions. Regardless of his reasons, his first step will further fuel the successful efforts of regional NGOs. Real change on deep-seated cultural issues has to come from within the culture and the efforts of regional NGOs are shrinking the cultural acceptance of shark fin soup. Jinping’s next steps should be to ensure transparent fishery landing data and trade reporting to the FAO and spread the ban on shark fin soup to the general populace. To be sure, even if the market for shark fin is eradicated, sharks and other marine megafauna will remain particularly vulnerable to bycatch in world fisheries. Global fishery management needs a major overhaul to address predominantly unsustainable fishing worldwide. E.O. Wilson wrote that, “destroying rainforest for economic gain is like burning a Renaissance painting to cook a meal.” This analogy is also apropos to sharks in that fishing out the world’s sharks for bowls of shark fin soup is like burning all the paintings in the Louvre to keep warm overnight.

Author Bio

Joseph Cavanaugh is a marine scientist living in St. Petersburg, Florida, USA.