|

|

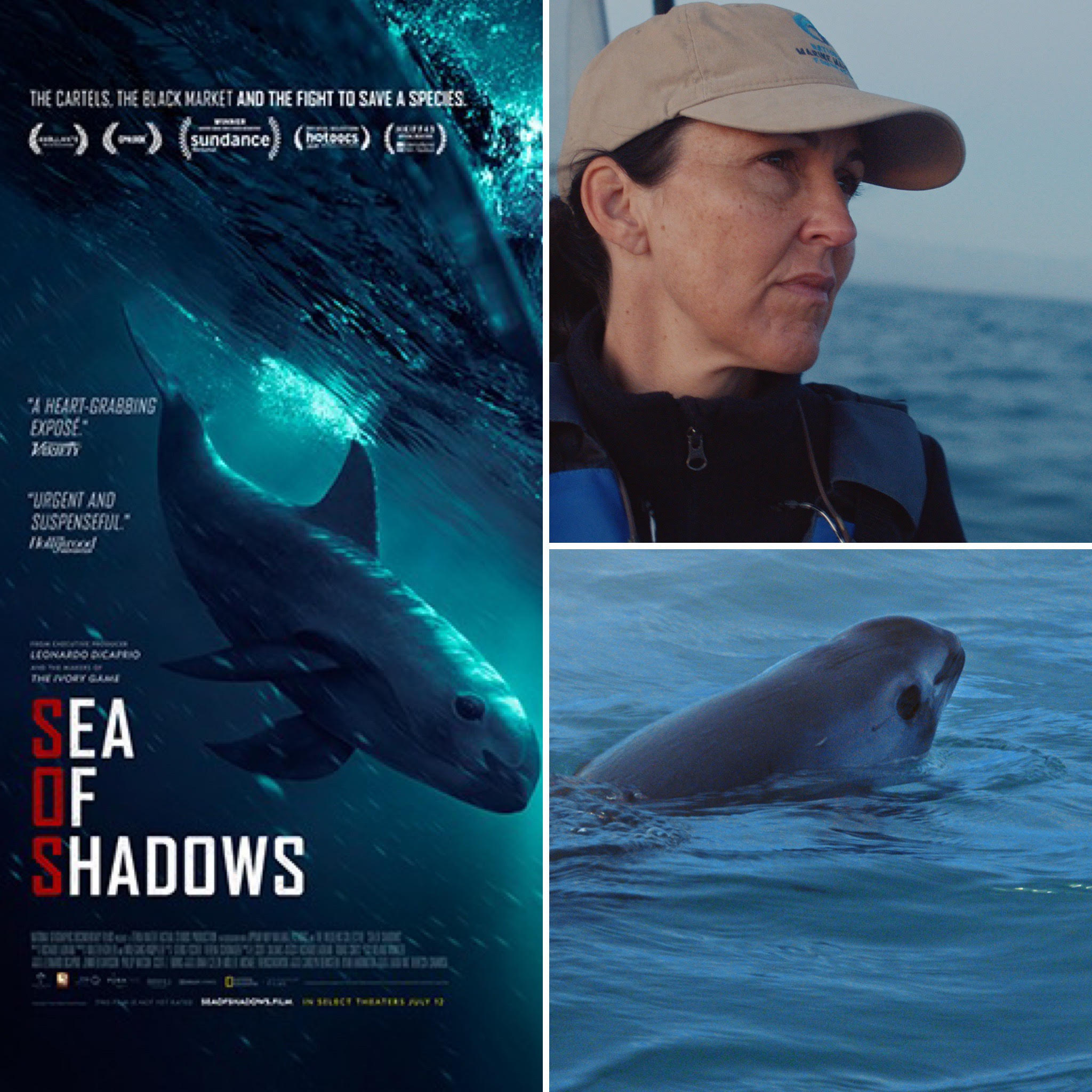

Sea of Shadows, an investigative documentary, examines how demand for toatoba bladder may wipe out the vaquita. Dr. Cynthia Smith (pictured) is featured in the film. SCB has urged governments to enhance protections for the few remaining vaquita. |

The conservation of the vaquita has garnered support from scientific organizations, celebrities, and activists, but perhaps no appeal to protect the species will hit harder than Sea of Shadows, a new documentary that meticulously uncovers how demand for toatoba bladder may wipeout what's left of the world's rarest marine mammal.

Dr. Cynthia Smith, executive director of the National Marine Mammal Foundation, is featured prominently in the film. Her team VaquitaCPR attempts to capture a vaquita to assess its ability to live under human care as a last ditch effort to save the species from extinction. She spoke to SCB about her role in Sea of Shadows.

|

---------------------------- "The story of the vaquita shows that it is never too early to contemplate what may seem like radical measures to halt species decline" Cynthia Smith ---------------------------------------------- |

Why did you decide to participate in the filming of Sea of Shadows?

Cynthia Smith: VaquitaCPR was a bold, urgent effort to save a species from extinction. Our management team recognized the importance of documenting that effort for scientific purposes as well as to inform the general public about the conservation crisis. As soon as the VaquitaCPR program plan became public, we began receiving offers from documentary filmmakers that wanted to help us accomplish both goals. Ultimately, we choose to work with director Richard Ladkani given his experience on other wildlife conservation films, most notably The Ivory Game and Jane’s Journey. Our hope was that Ladkani would capture the many facets and challenges of the VaquitaCPR project, raise global awareness for the plight of the vaquita, and spark an urgent conversation about ending species extinction. With his film, Sea of Shadows, Ladkani has done just that.

What did you learn from participating in the film that you can share with other scientists who wish to engage with storytellers / filmmakers who are working to expose corruption / shine a light on species conservation?

Cynthia Smith: Working with the filmmaker, Richard Ladkani, began as an exercise in trust. He worked hard to convey his genuine commitment to getting the story right and to furthering our conservation actions. Once trust was established, we began to let him in to the more vulnerable, human aspects of the project. Eventually, he was embedded on the boats, shadowing our project leads, and capturing historic footage of vaquitas. It certainly took some courage to allow him into those moments, but thank goodness that we did. My hope is that more veterinarians and scientists fully embrace the power of film and its ability to translate our efforts into something that is tangible, understandable, and compelling. And when doing so, it is essential that we choose filmmakers, documentary producers, and other storytellers carefully, making sure they are committed to operating in a way that supports the full realization of project goals and demonstrates that they truly care about the problems we are tackling.

|

|

Vaquita (Phocoena sinus) are found only in the Gulf of California. Recent estimates place fewer than 30 individuals alive today. |

What can governments and the general public learn from the plight of the vaquita to improve efforts to save other species threatened by extinction due to wildlife crime / illegal trade in species?

Cynthia Smith: Organized crime, corruption, and totoaba trafficking have substantially impacted the ability of vaquita conservation action plans to succeed. The tragic state of the species offers us an important opportunity to examine the depth of our commitment to mitigating these powerful threats to wildlife. How much effort and resources are we putting toward wildlife crime and does it match the enormity of the issues? Are we doing enough to incorporate local communities, some of which are being held captive by organized crime elements, into the plans and potential solutions? Are we exploring options for ex situ conservation - to buy species more time while we combat these threats - when there are thousands of animals remaining, not dozens? The story of the vaquita shows us that it is never too early to contemplate what may seem like radical measures to halt species decline. Within a few short years, hundreds of animals can rapidly disappear, seemingly dust away before our eyes. If we are willing to explore bold ideas early, we will have a much better shot at saving species from extinction.

What advice do you have for young conservation biologists who are working to save species that like the vaquita that are on the brink of extinction?

Cynthia Smith: Be courageous, be collaborative, work across disciplines, set aside your differences, and find common ground. Because ultimately, we all want the same thing - to save species. Study the extraordinary example of VaquitaCPR, where 90 individuals representing 22 organizations from 9 countries rose up together to meet an enormous challenge. Scientists, veterinarians, conservation biologists, zoologists, animal care specialists, academics, government officials, business owners, local community leaders, philanthropists, fishers, builders, educators, activists, communicators, and filmmakers. Learn from this group by opening your mind to others and finding that common ground, because it is a powerful space where surprising, humbling, and ground-breaking things can happen.

What non-science based skills should scientists hone to improve their effectiveness in making their science matter to the general public?

Cynthia Smith: When we embarked on VaquitaCPR, we leaned on a team of communications professionals to help us better communicate with the public. They encouraged us to speak to the stark realities of the situation even under difficult circumstances, and to speak with our hearts as much as our scientific minds. They encouraged us to show our compassion to the public, to allow them to connect with our mission and support us from afar. As it turned out, it would have been difficult to handle ourselves any other way, as the heart-wrenching status of the species was a looming pressure present during every conversation and addressed by every reporter. For the most part, I believe we were able to balance our scientific perspective with the raw emotion of the situation. And when we struggled, the investment we had made in connecting with the public in a very honest way came back to us in the form of overwhelming support, as they rooted for vaquitas and the survival of the species.