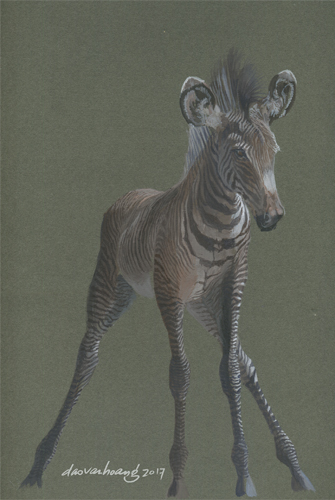

Gangly Long Legs

By Anne-Marie Gordon

The Grevy’s zebra (Equus grevyi) is among the world’s rarest equids and the largest zebra species, distinguished from the plains zebra by its large fuzzy ears, fine intricate stripes, gleaming white belly, soft brown muzzle, and a charcoal dorsal stripe bordered by a white space at the rump. The species is restricted to Kenya and Ethiopia, with Kenya hosting over 80% of the global population. It is one of Africa’s most endangered large mammals with population estimated at fewer than 2,500, and threatened by habitat loss, limited access to water, poaching and disease.

|

|

Grevy’s zebra foal; Gouache on board 8 x 3 in by Dao Van Hoang ©2017 |

Besides the thrill one gets when seeing young foals in a herd, it is also an encouraging sign, and indicative of a healthy population. Grevy's zebra mares are generally found together with other females in similar stages of reproduction. Their gestation period is 13 months, after which one foal is born, all gangly long legs and big fuzzy ears. After foaling, mares are solitary for a few days before joining other mares with foal at foot. Grevy’s zebra foals begin life by learning to distinguish their dam in the herd, gambolling, exploring and, finally, getting to know their peers.

By forming groups with other mares and foals, the mother provides her foal with an opportunity to interact with its cohorts. When conditions are good, foals are able to engage in play bouts, with the motor actions involved in play being similar to those needed for fighting and escaping predation. In addition, mothers benefit from being in groups with other foals as the probability of detecting predators is increased while the probability of her foal being preyed upon is reduced.

|

|

Mare with foal; Mia Collis/Grevy’s Zebra Trust. |

When lactating, a Grevy's zebra’s water requirements are high. As foals do not drink water before 4 months of age, they are fully dependant on mother’s milk until then. Foal survival is highest when lactating mares have immediate access to safe water sources as they don’t need to leave their foals for long periods, nor do the foals have to follow their mothers across a potentially dangerous landscape. Generally, foals follow their mothers from within a few hours after birth until weaning.

The mares tend not to take their foals along when the distance to water may be too far for a foal to travel. They leave their young in crèches for up to eight hours during the day, which enables the dams to travel greater distances from their young to drink during drought. But in areas with high numbers of human settlements, Grevy’s zebra change their behaviour and drink at night to avoid competition with cattle and disturbance from humans. In these instances, crèches don’t work because of the threat of predation. This predation threat is greater the further the distance the mare and her foal must travel between grazing and water, which is the case in the long dry season when the energy burden is at its peak.

Anne-Marie Gordon is the grants and communications manager at the Grevy’s Zebra Trust (GZT).