ACT - Volume 9 Issue 1

<<< Back to Table of Contents

Meet the Conservationist - Ivo Strecker

By Murali Pai

An Ivo-cative Life with Hamar

I ran into Prof. Ivo Strecker on a chilly November day in Arba Minch. He is an anthropologist who studied at the London School of Economics (LSE) and has worked with the Hamar in southern Ethiopia for 44 years. He is emeritus professor at Mainz University, located 30 km from Frankfurt, and currently is visiting professor at Mekele and Arba Minch Universities. He also founded and for more than 10 years directed the South Omo Research Center in Jinka, capital of South Omo. Now he mostly resides in northern Germany with his wife Jean Lydall, a renowned British anthropologist and film maker. For his unflinching service as an educator and love for the Hamar and their way of life, ACT is proud to name Ivo Strecker as conservationist of the month – Ed. Pai

|

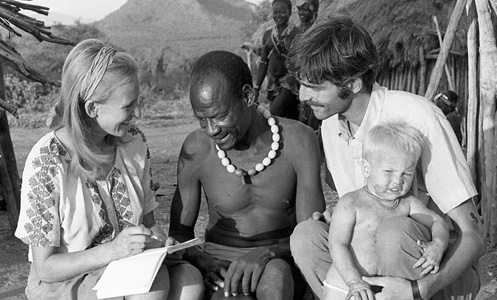

| Ivo Strecker (right) in 1970 with his infant son and his spouse Jean who is interviewing a local Hamar man in Ethiopia. |

Pai: How, when and why did you and Jean become interested in the Hamar of Ethiopia, out of an array of interesting tribes in Africa?

Ivo: We studied at the LSE and each had separate regional interests for fieldwork. Jean with the Huli in the New Guinea Highlands and I on Ternater and Telora, ancient strongholds of pirates and entrepreneurs in the East Indonesian islands. But when we met and finished studies we wanted to do something completely different. We found in London at the International African Institute 3 books of the Frobenius Institute on southern Ethiopia. This was an outstanding fresh survey of cultural diversity in southern Ethiopia and inspired us to travel there in the late sixties at a time when the country had opened up to research studies under the watch of Emperor Hailie Selassie. The ancient lure of Ethiopia was at its zenith.

Pai: How do the Hamar relate with the other Omotic tribes and the Nilo-Saharan and Cushitic tribes as well.

Ivo: The rift valley has created a topography that provides different tribes their own habitat. In southern Ethiopia, north Kenya and Sudan, 3 major linguistic families meet; the Nilotic, Omotic and Cushitic. The southernmost group in the mountain range between the Omo and Woito rift valleys is the Hamar. They split into 2 moieties, composed of some 30 clans in all.

Pai: Who are the allies and enemies of the Hamar?

Ivo: The Hamar are the southernmost Omotic group and relate with the tribes from the northern mountains such as the Ari, Banna and Bashada owing to linguistic and cultural similarities. Of course, we speak of a time before the advent of cell phones, internet and earth moving machines.

To the East is the Cushitic group with whom they have mutual raiding ties viz., the Borana. Both steal cattle belonging to each other, but they try to make peace. With the Arbore, the Hamar have had peaceful relations for over 30 years now.

To the West, with the Nilotic groups, Hamar have a history of war and peace. In more recent times, there has been harsh fighting with the Nyangtom. To the South, with the Dassench they have a tenuous relationship because they share some terrain, pasture and water, and there are too many opportunities to fight and kill each other.

Pai: What is the cultural uniqueness of the Hamar and how has it been affected by changing times?

Ivo: The Hamar are lucky in that they have an institution for which they are known far and wide, the Ukuli, a male rite of passage, which leads into adulthood. This event in which a youth leaps over a row of cattle is semi-public and may be witnessed by neighbors, visitors and even tourists from far afield without causing irritation. The Mursi, who also live in the Valley of the Lower Omo, are less lucky. Their most spectacular cultural feature is the large plate that a Mursi woman wears in their lower lip. Tourists come from all over the world to stare at them and take photographs of these in their view extraordinary women. Needless to say that the Mursi experience this as an affront.

But back to the Ukuli: The initiate is called Ukuli (donkey) because the sexually improper life of his youth has ‘polluted’ him. Once he leaps over the cattle he gets purified and can from now father legitimate children with his wife. Just before he leaps, the initiate stands in the middle of a herd of cattle belonging to his family and clan. Then the cows are brought into a row sandwiched between two oxen and the Ukuli jumps on top of the ox and then runs across the cows. He does an encore when he gets to the other side. In front of the first ox is a calf of which he becomes the father and he is henceforth called after the color pattern of the calf.

This rite of passage allows the young man to marry, and the marriage is binding for life with no possibility of divorce. The man symbolically wears the skin of a dik-dik antelope around his belly and the wife adorns a piece of the same skin around her neck. When the wife attains menopause, she and her husband will decide whether he should marry a second wife to have more children and to assist the ageing wife with her work.

Part of the ‘Ukuli’ is the whipping of women at the ritual. The whipping wands draw blood and cause scars on the backs of women who are real or classificatory ‘sisters’ of the initiate. Although this may appear cruel the whipping is justified as follows: The ‘sisters’ will later go to their brother and show him the scars as non refutable proof of their devotion to him, - and then they will demand livestock from their brother in return for the blood shed at his rite of passage.

Pai: How have the socio-economic and ecological practices of the Hamar impacted the biodiversity?

Ivo: About 100 years ago, the high plateau of Hamar country used to be grasslands teeming with wildlife like the savannahs in the lower Omo valley. Now the high plateau is covered with thorny bush as a result of over grazing. But the bush is still a good resource for goat rearing and the Hamar are among the best goat herders in the country. In order to counter the loss of pasture the Hamar recoup grasslands by fencing in stretches of land. Here, inside the ‘darr’, wild grasses will eventually grow again. So the ‘darr’ is a good example of controlled grazing practiced to this day.

Pai: Describe the wildlife you sighted in the early days of your work?

Ivo: When Jean and I arrived almost a quarter of a century ago, Hamar country still abounded with antelopes, greater and lesser kudu, ostriches, zebra, buffalos, giraffes, lions, wart hogs, and so on. We witnessed how with the advent of new roads and the traffic, the wildlife began to disappear. Also, we saw how arms and ammunition trickled over from wars in South Sudan and Somalia, although South Omo itself was never a war zone. This arrival of ever more arms and ammunition meant the death of almost all of the last remaining wild life in the South Ethiopian Rift Valleys.

Pai: What will be the fate of the Hamar with all the changes in the industrial and agricultural landscapes? How can the government help to cope with the situation?

Ivo: The new fast-track development mooted and practiced by the government of Ethiopia in South Omo has resulted in large-scale industrial and agricultural projects, mainly sugar and cotton plantations. These will in turn spawn big factories and ginneries with an overall increase of migrant labor from far afield. The Hamar could be suppliers of fresh meat to this new population, given their expertise in goat farming. They could also reorganize and adjust their herding practices to sync with the new farms and even make deals with large scale projects to provide watering places for their herds. Also, byproducts of large-scale agriculture could be used as livestock feed ingredients. For instance, molasses can be obtained from sugar factories. Therefore, there can be equitable development.

Pai: Tell us about projects that put aforesaid ideas to practice?

Ivo: I am now beginning to work with Awoke Aike, representative of the Hamar in the National Parliament in Addis Ababa on the Hamar Integrated Pasture Project (HIPP). This is to integrate the resources and know-how brought by the new large-scale agricultural projects with the opportunities afforded by the local knowledge competence of the Hamar. So, in my view, the subsistence lifestyle of Hamar in their highlands will not be too badly impeded by the winds of change blowing in the lower valleys.

Murali Pai is the Editor of ACT and a faculty member at Arba Minch University, Ethiopia.